Image from Flickr by AmyLovesYah

Gabriel’s teacher recently invited me to talk to her second grade class about being an author. She had read my novel and, having particularly liked the first pages, hoped I could frame a discussion around word choice and the importance of beginnings.

I had all sorts of thoughts about how this would go. At their age I’d already fallen in love with language and kept a notebook filled with favorite words. The meanings of words mattered, of course, but even more intriguing were the sounds they made.

And when the sounds matched the meanings, like in “chime” and “thick” and “secret”? Well, that was pure magic.

So I thought I’d talk to the kids about my notebook, the excitement of discovering new language, how I’d open the dictionary to a random page, scan the possibilities, sound out syllables and make crucial choices about which gems to inscribe in my little spiral notebook (the lines more blue than green, the margin line more pink than red).

This would lead to a discussion about word choice, because authors must not only love words but love them enough to choose them wisely.

Which would lead to a discussion about the importance of beginnings.

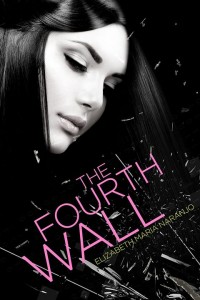

Good plan, right? But in the end none of that happened, because the kids led the discussion. All I had to do was read the first page of The Fourth Wall, and then the students responded with a flood of questions.

They asked me how I felt writing the book at sentence level, how long it took, when I knew I wanted to be an author, and so on. And then the teacher directed them to write their own beginning, a single paragraph, with an illustration. After maybe fifteen minutes, the kids began to share their work.

Their stories varied widely. Some had magic, some had monsters. Some were cliffhangers, some complete tales. Some had detail and others were straightforward and concise.

Gabriel’s story involved a machine—complete with levers and buttons and compartments that held some sort of mysterious dye.

One girl wrote in third person about a child who wondered what two mean girls, whom she described as friends, really thought of her. While reading aloud, she accidentally switched to first-person narration and abruptly stopped. She looked confused and went to erase something on her paper, murmuring to her teacher that she’d made a mistake. Her teacher said it sounded fine, and the girl quietly finished her story.

When it was time to line up for the bell, kids kept sneaking over to talk to me. A blue-eyed towhead, who’d said the first page of my book scared her because she doesn’t like monsters, told me, “Now I want to be an author like you.”

Another girl, who is always outspoken and precocious, asked me boldly for the name of my publisher and their email address.

As you can imagine, my heart was pretty much soaring at this point. I loved hearing the kids’ stories and seeing their starry eyes and answering their surprising and sometimes adorable questions, all starting with “Miss Elizabeth?” I loved how my son held my hand firmly on the way out of the classroom. And I loved how, on the way to parent pick-up, one of the boys skipped up to me and asked me this last question of the day:

“Miss Elizabeth?”

“Yes?”

“Will you tie my shoe?”

Connect With Me